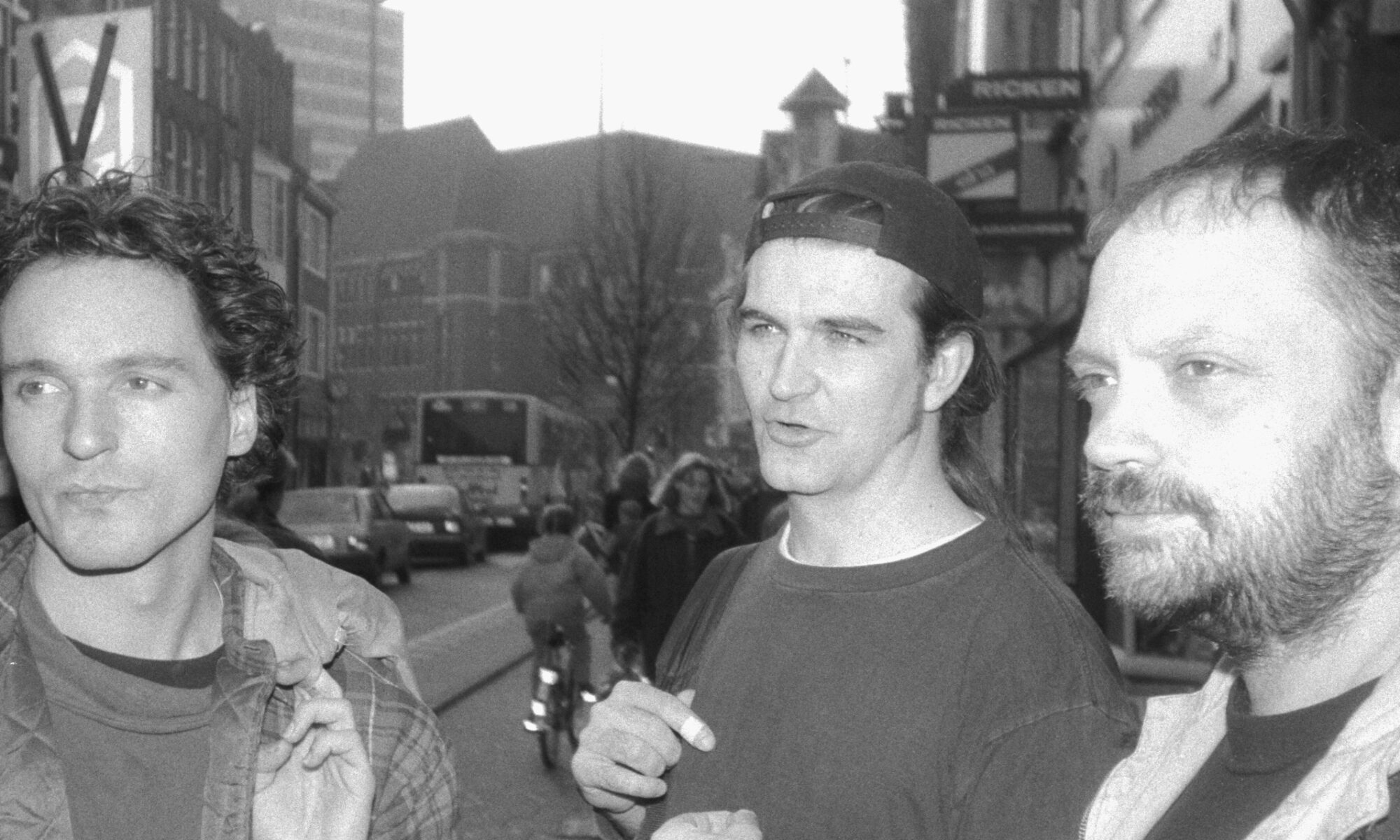

From escaping the confines of his Berlin home at 16 to signing on at sea and traveling the world only to be thrown overboard in a disagreement with older sailors, Thomas Schulz has always had his very own point of view.

By 1977 he is working as a stonemason, when he is invited by Shinkichi Tajiri to study fine arts at Berlin’s Hochschule der Künste. He thus begins his journey into sculpture where, while working on a series of figurines, he realizes that the conventional sculpting with stone and bronze is not suitable to match his vision of art. He destroys his unfinished figures and begins to look deeper, fascinated by the appearance and disappearance of all material. And his investigations and reflections now often start with a sound that crawls into his ears first and points to a subject.

He starts, as he explains, playing with everything that gets the attention of his hands, his ears and his eyes. Over time he creates a large body of work that is less defined by single pieces of art in any of his numerous exhibitions from New York’s PS1 to Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, to Kyoto’s Art Space Niji.

It is an always growing large organism that manifests itself only when he places it at a specific space to be exhibited, performed, photographed, filmed, written down, or put into a radio broadcast vessel. An organism that materializes at the very spot it will be seen or heard.

The year 1981 marks the first creative explosion of his research. In ‘Faced Mirror’, filmed at DAAD Gallery Berlin, he outlines a human body with screws in a bare wall. The screws are connected with 180 steel wires to 360 points to the walls of the room. In the final act he tightens the tension of the wires until the figure is ripped off the wall with a deafening noise, transcending the boundaries of the body, the room and the connection in between.

In ‘Vom Eiskeller zur Osterweiterung’ (roughly literal: from ice store to the enlargement of the east) he not only shakes the limits of the material at hand but also the very real borders that surround the enclave of West-Berlin. He spans a net of wires and glass along the Berlin wall and starts to play the installation as an instrument, with a cello bow and various construction tools. In the face of the no man’s land separating the two Germanies he suddenly turns into an intrepid reporter interviewing voiceless East-German soldiers who are busy burning the grass between the spiked field on one side and the bricks of the Berlin wall at the other.

Sculptures of steel wire and geometric glass panels are a subject Schulz is faithful to through all of his artistic life. They span rooms of lost warehouses and exhibition spaces, at times expanding into the surrounding landscapes. They are abstract room-filling sculptures, moving paintings, architectural and topological comments to the man-made cultivation of the space on earth, and not the least, oversized musical string instruments and reverberation chambers, all at the same time.

Installations are but one of his methods to explore spaces and buildings. When he has to leave the temporary home Schulz used to inhabit with fellow artist Ronald Steckel, amongst others, a feature long audio piece remains as a memorial of the location, using found sounds of the building, everyday noise of the inhabitants, sounds collected from in-house performances and spoken word experiments. A later version of ‘Das Haus Spricht‘ (the house talks/the speech of the building) will then finally be projected to Berlin‘s Mies van der Rohe Haus (2020). Speakers turned against the outside of a large glass front now make Mies‘ building literally tell the audience from Schulz former and lost residency at Wannsee.

In ‘Vektor 1’ he tightens wires through ice blocks on the frozen surface of Lake Wannsee to observe the crashing noise of the slowly moving ices. In ‘Kleine Eiszeit’, Ice Blocks hanging in a mesh of steel wires in the garden of Hochschule der Künste, “make the wires sing, (…) and the melting of the ice audible”, as art historian Shin Nakagawa describes in an essay (Heibon-sha, Tokyo 1997). Further research later finds Schulz at very different places like the Bundesamt für Materialprüfung (Federal Office for Materials Testing), recording very low level sounds – termites – as well as the extremely heavy sounds of huge bursting metal plates.

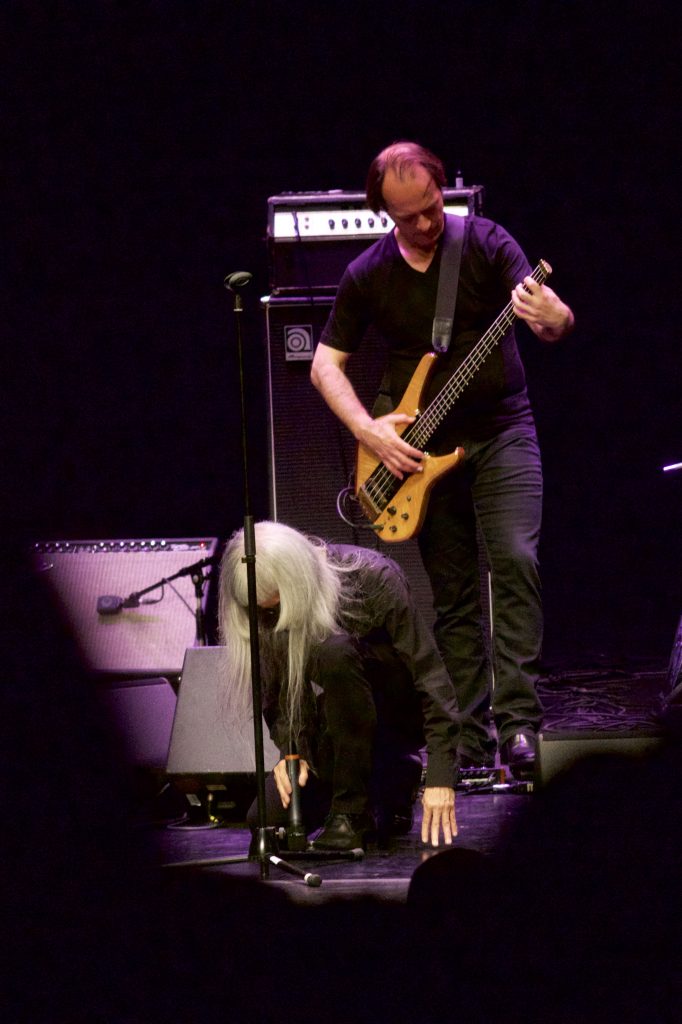

While Schulz has predominantly been perceived as a visual artist, he has continuously been as much a sound researcher and sound designer and a musical improvisor as well. He performs with Marino Zappelini (Sax) and opera singer Jane Smith at J.J.Donguy (Paris 1982) and meets Shelley Hirsch, with whom he shares a longtime friendship, at Büro Berlin. In a late performance 2016 at Galerie Neu West Berlin, a former supermarket turned to a temporary gallery space, he plays a sculpture that extends from entrance door to the very back of the former market space. The program of the evening also lists Peter Brötzmann, Olaf Rupp, Kalle Kalima and Michael Wertmüller.

Late 70s Schulz had started to search scrap metal heaps for recyclables he could use in his work. He welds scrap into pieces of seemingly unstable, but actually usable furniture, kinetic sculptures and musical instruments as well, that then become objects he treats in his performances. Sculptures that are reminiscent of Calder as much as of Tinguely, as he likemindedly and playfully sculpts material, form and sound.

Early 1980s he performs at the same places and times with other artists who channel the desperate situation of Berlin’s west into art. Die Einstürzenden Neubauten also play on used metal, yet mostly out of the necessity to find affordable instruments (later writing more conventional songs, when they have the means to do so). Die Tödliche Doris, as Wolfang Müller explains, “suddenly got unexpected interest by the pop world”, and thus begin experimenting with pop culture. Schulz, however, is always an explorer in the material itself and in the pure nature of sound.

Thomas Schulz mentions listening to John Cage and attending an early concert of the Seesselberg brothers in his youth, as being an awakening for his interest in sound and composition, but when asked, claims, that he has had no interest in using electronic instruments “as long as we haven‘t explored the endless possibilities the acoustic sounds of the materials offer when you put your efforts into listening and into treating them.“ And matter, to Thomas Schulz, always has its own voice, as one of his titles points out: ‘Die Rede in den Stimmen des Materials‘ (the speech in the voices of the material).

Schulz’ biggest and rather monumental endeavour is what he calls ‘The European Sculpture‘. A reflection on the growing European state-like building, which he studies in a two year accreditation with European Parliament vice president Hans Peters in Brussels and Strasbourg, and in repeated visits on the construction site of the Eurotunnel from 1989 to 1996.

At the European Parliament he photographically documents the construction of the new buildings necessary for the growing union and records simultaneous translators. Material he later uses in various arrangements and cut-ups in audio pieces and in installations he calls Mikrophonien (mircrophonies): grouped microphones that, instead of listening as they are intended to, are talking to the visitors.

At the Eurotunnel he gets access to all areas of the construction site, guided on the French side by representative William Coleman. Schulz then records large parts of his visits on a field recorder and documents the construction process with his two-eyed 6×6 camera as well. ‘The European Sculpture …not here but under the sea‘ (Bayrischer Rundfunk, BR, 1992), tells the story of a trip on the site where England and France would eventually be connected, underneath the sea, a story of the workers who make this happen and of the construction machinery that talks and sings to us but will be buried there forever.

Thomas Schulz incredible large library of unusual sounds, from field recordings to recordings of performances, to the echo of his own heart, as heard through an ultrasonic medical device, to language experiments, are the basis for a series of compositions, most of them commissioned by German public radio stations. As a composer and performer he’s also been invited three times to Musiktage Donau-Eschingen, Germany’s most important festival for contemporary classical music. ‘Die Vier Seiten in 23 Sätzen‘, produced by the Studio Akustische Kunst of WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk, Köln, 1990), in cooperation with SFB (Sender Freies Berlin), is the exemplary masterpiece showing Schulz’ perception of the audible world “in the voices of the material”: acoustic landscapes, his involvement with materials and people, to eventually taking an unexpected turn into a fragment of a light pop song with a strong beat, composed of samples from his collection.

In memory of Thomas Schulz (1950-2021)

Manuel Liebeskind, Berlin 2023, with thanks to Eugene S. Robinson, Veronika Kellndorfer and Helga Lutz.

These are the original liner notes for the Thomas Schulz Album not here but under the sea, released by Skin and Speech Records, November 2023

Thomas Schulz – not here but under the sea

Skin and Speech Records 2023